Further information about leak

Published 11:02 am Friday, May 18, 2018

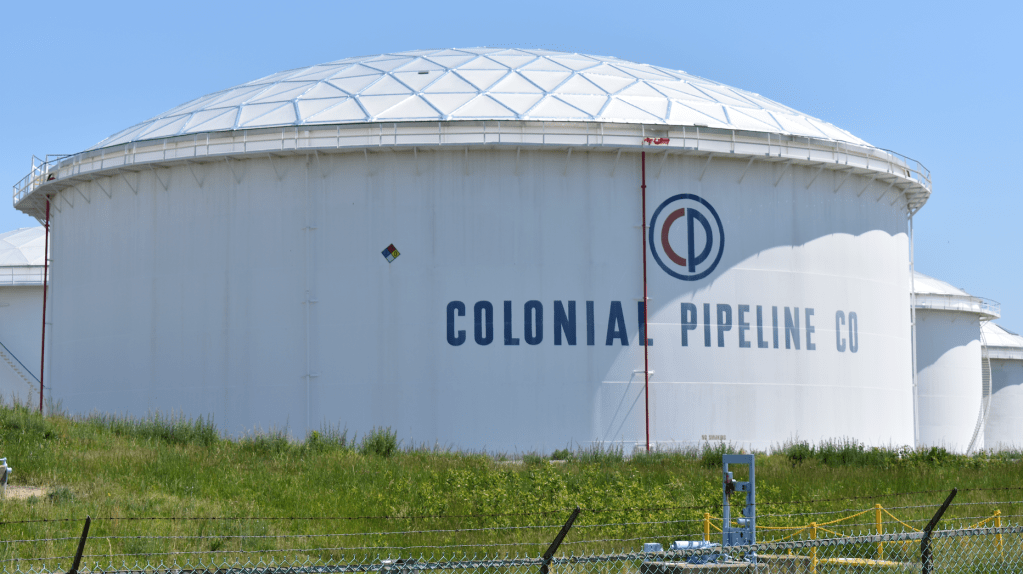

- Colonial Pipeline’s Mitchell Junction tank farm on 425 Duncan Store Road in Columbia reported a gasoline leak May 3. (Photo by Emily Hollingsworth)

Approximately 3 gallons of gasoline were released from a gasoline leak at the Mitchell Junction facility that took place in Columbia, near Cumberland County, May 3, a Colonial Pipeline spokesman said.

The May 3 incident resulted in emergency service personnel from Cumberland County, Powhatan County and Goochland County responding to the leak, Cumberland’s Fire and Emergency Management Services (EMS) Chief Tom Perry said during a Cumberland County Board of Supervisors meeting. Perry said personnel worked 28 consecutive hours to repair the leak.

The Herald reached out to Steve Baker, Colonial Pipeline spokesman about the cause and impact of the incident.

The cause of the leak Colonial Pipeline reported, according to Baker, was a crack in a seam weld from a previous repair.

“We reported to (Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration) PHMSA that we had a small crack in a seam weld from a prior repair,” Baker said.

PHMSA is an agency from the United States Department of Transportation that regulates pipeline transportation and infrastructure.

Baker said Colonial Pipeline ships approximately 2.5 billion gallons to Virginia annually.

When asked by The Herald what the reach of the gas leak would have been and if there was any impact to residential or business properties nearby, Baker said, “Given the small volume released, there was no plume. And there was no impact to neighboring properties. The gasoline was contained within Colonial’s facility and, as Chief Perry said, there was no threat to residents.”

A plume describes the discharge of the gasoline as it travels through water or soil.

Bill Wellman, of Farmville, has had experience in command with The Navy Petroleum Office, or the NAVPETOFF, an organization responsible for all aspects of fuel support for the Navy and Marine Corps. Wellman said he has also worked in a fuel complex in Jacksonville, Florida. The Herald reached out to Wellman to learn more about operations relating to gasoline and fuel industries.

“Gasoline, in particular, is highly volatile, and the fraction of discharge lost to evaporation could easily have exceeded—greatly—the quantity recovered,” Wellman said. “Furthermore, because the discharge was not directly into the retaining pool where collection was made, some amount of fuel infiltrated the concrete and the soil. If that discharge saturates the soil and subsoil, or even the bedrock, the petroleum creates a plume that moves underground with, possibly, no above-ground evidence. While there exist very expensive fixed systems that could prove or disprove existence of a plume immediately, normally it takes a few weeks to install monitoring wells to determine the extent of plumes. An immediate report guaranteeing no plume—without description of how that is known—is unusual.”

“Large petroleum shipments are often defined by Mbbl, or thousands of barrels,” Wellman said. “There are 42,000 gallons in a Mbbl.”

Baker said Colonial Pipeline uses a standard measurement to measure gasoline, similar to how gallons of gasoline are measured in gas stations.

“At the time Colonial requested the fire department’s help, it had not identified the amount of gasoline present,” Baker said. “The request for support was a safety precaution by Colonial, and we appreciate the fire department taking prompt action. Colonial measures volume the standard way — 3 gallons is 3 gallons regardless if it is measured at our facility or a gas station.” Regarding the lack of plume, Baker said the retention pond is meant to operate as an early warning system for any potential issues.

“The retention pond was visually inspected and a sheen was detected,” Baker said. “Once detected, the operators contacted the control center and the local responders to initiate a response. The investigation confirmed that a total of 3 gallons was released from a previous repair on the pipeline and that there was no evidence of a plume. A retention pond is not the same as a monitoring well. In this case, the pond within Colonial’s facility served as an early warning system and prompted us to ask for the fire department’s assistance as we identified the source and completed the repair.”

A monitoring well, Wellman said, is a small well drilled to examine water quality at a particular underground point

The Herald asked Baker and Wellman about the flash point of the gasoline at the facility.

“A flash point is the temperature at which a spark, with no additional heat, will ignite a particular fuel,” Wellman said. “If this was a gasoline discharge, almost certainly the evaporated product was volatile enough to explode with just a spark if the fuel-air mixture were neither too rich nor too lean. If the product had ignited, the blast and ensuing fire would have been very significant, significant enough to endanger lives as well as property.”

Baker said the standard flash point for gasoline is -45 degrees Fahrenheit, the same flash point for a motorist filling a car tank. He said due to first responders’ quick work, there was no threat to the facility or those nearby.

“Colonial does not have a product specification concerning the flash point of gasoline. But the standard flash point for gasoline is -45 degrees Fahrenheit,” Baker said.Baker said the product specification Colonial Pipeline uses is related to the quality of the product.

“Colonial’s product specifications are centered around the quality of the products we are transporting,” Baker said. “An example of a product spec would be octane or RVP (Reid Vapor Pressure).”