Book review — James Dickey: A Literary Life

Published 4:09 pm Saturday, April 16, 2022

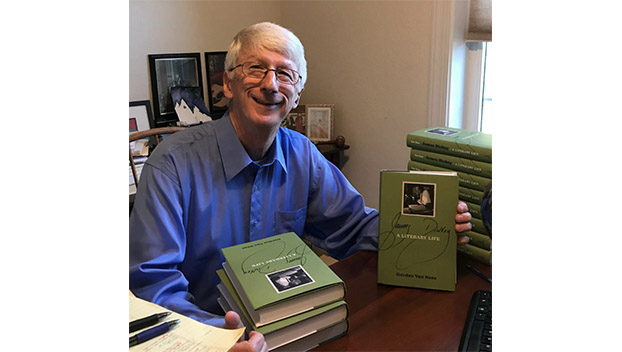

- Dr. Gordon Van Ness with his latest book, James Dickey: A Literary Life.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Dr. Jes Simmons

Retired Longwood English Professor and Administrator

Dr. Gordon Van Ness is a class of 1972 graduate of Hampden-Sydney College who became a professor of English at Longwood College (later University) from 1987 until his retirement in 2018. A notable scholar of poet and novelist James Dickey, Van Ness has just written what promises to be the definitive literary biography of, arguably, America’s most confoundingly admired and dismissed poet. James Dickey: A Literary Life is forthcoming early this May from Mercer University Press, and joins his four other scholarly significant books about the writer, beginning with Outbelieving Existence: The Measured Motion of James Dickey (1992), Striking In: The Early Notebooks of James Dickey (1996), and his two-volume collection of the poet’s letters, The One Voice of James Dickey: His Letters and Life, 1942-1997. In 2015, with approval of the Dickey estate, Van Ness additionally edited and completed Death and the Day’s Light, the unfinished book of poems Dickey was writing and compiling before his death in January 1997.

James Dickey has been on Van Ness’ radar since his undergraduate days at Hampden-Sydney where he first read Dickey’s poetry in an English class. In graduate school at The University of Richmond in the early 1980s, Van Ness was encouraged to write his master’s thesis on Dickey’s ninth book of poetry The Zodiac (1976). Van Ness later chose to pursue a doctoral program at The University of South Carolina, where Dickey taught English and served as honored poet-in-residence. The admiration Van Ness held for the poet evolved in the next few years into a companionable friendship between the two men, who called each other Van and Jim. This connection is the crux and brilliance of James Dickey: A Literary Life for it allowed Van Ness access to and understanding of the poet’s personal self, even revealing not only Dickey’s aggressive insecurities hidden behind his self-aggrandizement, exaggeration, and even hoaxes, but also his non-poet persona as college football and track star, fighter-pilot war hero, daring white-water canoeist, and wildlife hunter armed with bow-and-arrow and blow-dart. This latter image was further enlarged by the stratospheric literary and financial success of Dickey’s first novel Deliverance. To further sustain this persona, Dickey sometimes flew to readings or hailed a cab while carrying deer-hunting archery equipment and a variety of guitars. Van Ness sees how sustaining the fiction only led to Dickey’s isolation from others, including members of his own family.

During the late fifties through the sixties, James Dickey became the public face of American Poetry (a capital P). His fifth poetry collection, Buckdancer’s Choice, won the National Book Award in 1966, and Dickey was named as poetry consultant twice for the Library of Congress from 1966 to 1968. In 1969, Dickey additionally had the honor of poetically voicing the nation’s pride in landing two Americans on the moon in a poem called “The Moon Ground” that was published in Life magazine and literally read aloud by the poet on national television on July 20, the day of the moon landing. Dickey’s rise to literary fame and public celebrity pinnacled when he published Deliverance in 1970, followed by the hugely successful film in 1972, in which Dickey himself had a role.

Most critics agree that Dickey’s footing at this pinnacle began slipping as in the late 1960s–personally from the effect of his increasing alcoholism and culturally from a shifting consciousness within America fueled by Civil Rights marches, Vietnam War protests, the women’s movement, Watergate, and environmentalism. The rugged and individualistic alpha-male swagger and exaggeration of Dickey’s public persona that also served as the heavy undercurrent of most of his poetry no longer spoke to or for the nation and specifically to its poetry-reading public.

Dickey’s literary and financial success from book sales and hundreds of readings at colleges and universities across the country — what he famously called “barnstorming for poetry” — robbed the poet of the necessary time to write. Social drinking before and after readings spiraled into alcoholism. The result, critics noted, was a softening of the poet, a lessening of his poetic powers and his energy as a writer. Yet Dickey did write quite movingly, stretching and flexing the possibilities of poetry and growing beyond those critics who preferred the topics and heft of his former poems and who showed an unsettled lack of surety or security with the growth and changes Dickey made to his poetry-lengthening lines, inserting spaces between words or clumped phrases, and hanging a mobile of lines down a page in balanced unbalance, or the poet’s shift to translating foreign poets through what he labeled improvisations or collaborations, as well as producing a spate of pricy coffee table books where his poetry interpreted or balanced the drawings, watercolors, or photographs of visual artists. Like the wild and swift-flowing Cahulawassee River in Deliverance slated to be dammed, tamed, and made into a recreational lake, Dickey’s larger-than-life presence and influence soon vanished.

What never vanished, though, was Dicky’s lesser-known success and influence as a university teacher. From 1963 to 1997, the poet was also James Dickey the university professor, deftly and brilliantly teaching writing and literature at different institutions of higher education until settling most comfortably at The University of South Carolina in Columbia, where he taught as distinguished poet-in-residence for nearly 40 years up until his death. Dickey’s strengths and methodology as a teacher beloved by students never seemed to wane or fall out of favor. In class, Dickey captivated and even mesmerized his students, whether speaking eloquently and eruditely about a vast range of poetry and poets or paternally encouraging his creative writing students, providing them with the confidence to reach toward being the best poets they could.

Van Ness knew James Dickey probably better than anyone else, and in James Dickey: A Literary Life, his unique radar penetrates the stealth technology of the poet’s self-created form to reveal Dickey’s vulnerabilities and fears, his sensitivity and many kindnesses. Van Ness writes assuredly and knowledgeably about the poet as a whole human being that few truly knew. In fact, “no one knew” is a refrain Van Ness carries throughout the book to help reveal the gentler and more humane qualities of James Dickey. Gordon Van Ness is one who knew, though, and this lens enables him to reveal Dickey as only he can.

Van Ness, in James Dickey: A Literary Life, may very well succeed in helping resurrect, re-see, and re-think Dickey’s poetry and career and thus restore James Dickey to significant prominence in the canon of American poetry, rightfully returning his poems to the pages of anthologies for current and future study.

In a recent email to me, Gordon lamented about Dickey, “I surely do miss him.” If Jim were here to comment on Gordon’s eloquent and perceptive James Dickey: A Literary Life, I believe he’d say, “Van, you did me right by that book. You did me right.”