Prince Edward NAACP sets up annual tribute to L. Francis Griffin

Published 3:43 pm Sunday, September 1, 2024

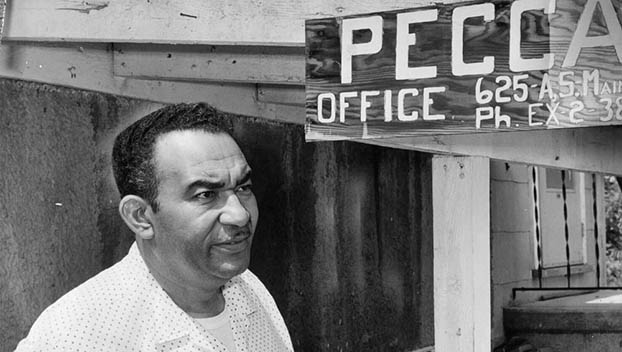

- Rev. Francis Griffin, who mentored the students in the 1951 strike and then took part in a Supreme Court case of his own more than a decade later.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

They want to make sure he’s not forgotten. That’s what members of the Prince Edward County NAACP say helped shape this tribute to Rev. L. Francis Griffin. The group decided to hold a ceremony on Monday, Sept. 16, the day after his birthday and turn it into an annual tradition, to preserve his memory.

“We are laying this wreath now to show our love and respect for our fearless leader and to make sure he is never forgotten,” said Prince Edward NAACP President James Ghee.

The plan calls for a wreath laying ceremony at 5 p.m. on Monday, Sept. 16, held at Rev. Griffin’s grave site in Odd Fellows Cemetery. That’s located across the street from the R.R. Moton Museum and beside Oliver & Eggleston Funeral Home. The ceremony will precede the regularly scheduled 6 p.m. meeting of the Prince Edward County NAACP chapter meeting. Members will gather at the R.R. Moton Museum and make their way down to the cemetery for the ceremony, then return to the museum for their meeting.

This isn’t a one-time event, Ghee said. He and the rest of the Prince Edward chapter plan to do this every year, honoring the civil rights pioneer on or around his birthday of Sept. 15. Now there are a number of memorials in his name, both here in Farmville and around the region. Two years after his death, for example, Griffin Boulevard in Farmville was named after him. The Virginia Civil Rights Memorial, which currently stands on the grounds of Richmond’s Capitol Square, has a statue of the man. And when you go over to Prince Edward County Middle School, you’ll find the L. Francis Griffin Sr. Gymnasium.

But in the midst of all that, the NAACP is concerned people may see the statute, read the street sign and walk into the gym, all without knowing exactly who Griffin was or what he did. That’s where the ceremony comes in, as an annual reminder.

Who was ‘the fighting preacher?’

The story doesn’t end with the Brown v. Board of Education ruling. In fact, reactions to that case sparked Civil Rights battles for more than a decade. This past May marked the 60th anniversary of a decision in Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, yet another Supreme Court battle.

Trending

Yes, we’ve heard of “massive resistance”, the fight by Virginia’s government against integration. But in Farmville and Prince Edward County as a whole, that took on an entirely different look.

Prince Edward County’s Board of Supervisors decided in June 1959 to not appropriate any funding at all for the school system, rather than integrate. That meant all public schools in the county had to close for what eventually became a five-year period.

Prince Edward gave tuition grants to students, instead of opening schools, to be used at private schools. But there were no private schools in the region that allowed Black students, so from 1959 to 1963, Black children in Prince Edward County were left out.

It was something an entire community had to deal with. Children were being kept out of the only classrooms available. A 1964 study done by Dr. Robert L. Green of Michigan State found that out of 1,700 Black school age children in the county, an estimated 1,100 had received almost no formal education during the period schools were closed. In the post-pandemic world, we discuss learning loss because students weren’t able to be in class for one semester or a full year for some. More than triple that and you start to have an idea of what was taken away.

And this is where Francis Griffin enters the conversation. That is, he enters the conversation for a second time. Rev. L. Francis Griffin was a mentor and supporter of Barbara Rose Johns and the other students in that 1951 strike at Moton High. He helped connect them with NAACP attorney Oliver Hill, which led to the legal case being filed.

People called Rev. Griffin the Martin Luther King Jr. of Farmville. He also earned a nickname as “The Fighting Preacher,” both locally and nationally. Griffin was focused on the social gospel during his life, speaking out against injustice whenever he saw it. The Farmville preacher’s words back that up, as he was repeatedly quoted as saying he believed “in the care of people here on Earth and in the hereafter,” following what he found in the teachings of Jesus. And while his own legal case may not be as well-known nationally as Brown v. Board of Education, it was in many ways a followup to that situation.

Prince Edward NAACP wants to remind people

Trending

Francis Griffin had several children were not allowed to attend any private schools since they were Black. As we mentioned, public schools in Prince Edward were closed at the time and private schools were just that, able to allow or disallow whoever they wanted. He filed a lawsuit, challenging the supervisors’ decision.

And so, for the second time in a decade, Prince Edward County ended up in court. This time, it also went before the U.S. Supreme Court, in the March 1964 Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County case.

After two months of discussion and debate, the justices ruled Prince Edward’s decision to close all local public schools and provide vouchers for students to attend private school was constitutionally impermissible. That’s because it violated parts of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Black students didn’t have the same opportunity as others in the district, because none of the private schools would accept them.

“The District Court may, if necessary to prevent further racial discrimination, require the Supervisors to exercise the power that is theirs to levy taxes to raise funds adequate to reopen, operate, and maintain without racial discrimination a public school system in Prince Edward County like that operated in other counties in Virginia,” justices wrote in the majority opinion.

Just as Barbara Rose Johns and her fellow students set a national Civil Rights standard, so did Francis Griffin. His Supreme Court case set a precedent, detailing that a county can’t withdraw or give up on its obligation to provide public education for everyone.

That’s what members of the NAACP wants to remind people of, both this September and every year to come.