Marsh gives address, book signing

Published 4:05 pm Thursday, June 28, 2018

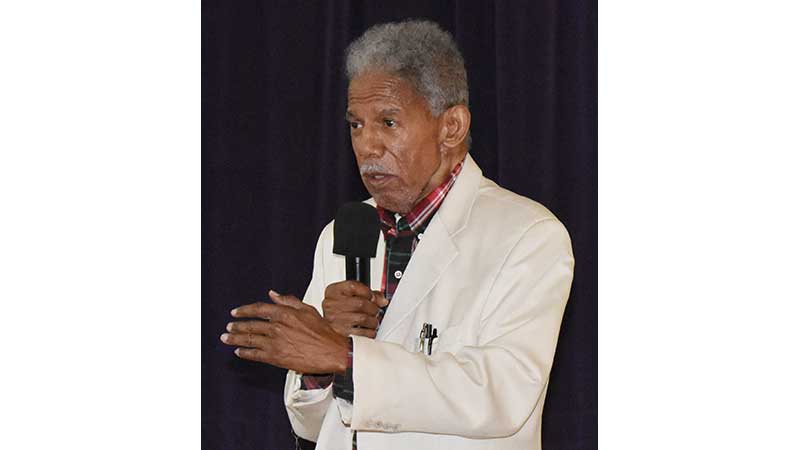

- The Hon. Henry L Marsh III, a civil rights activist who was the first African-American mayor in the City of Richmond, speaks to an audience at the Moton Museum. Afterward, the museum held a book signing for Marsh’s book, “The Memoirs of Hon. Henry L. Marsh III: Civil Rights Champion, Public Servant, Lawyer.” (Photo by Emily Hollingsworth)

The Hon. Henry L Marsh III, civil rights activist and the first African-American mayor in the City of Richmond, spoke to community members gathered at the Moton Museum Thursday.

Several of those who attended and introduced themselves had been affected by the closing of public schools in Prince Edward County from 1959-1964.

Following the keynote and question and answer period, Marsh signed copies of his recently-released book, “The Memoirs of Hon. Henry L. Marsh III: Civil Rights Champion, Public Servant, Lawyer.”

Trending

Marsh’s run in the Richmond City Council in the 1960s, then in the political sphere in the City of Richmond, served as a triumph during a time where local and state governments were resistant to black representation in public office, a challenge that continues into the present day.

Marsh has also advocated for equality and desegregation in Virginia public schools.

“The fight for human rights is unending,” Marsh said in his book. “We must never stop fighting for freedom and equality for all.”

Marsh was also instrumental in the state passing the “Brown v. Board of Education Scholarship Program,” a scholarship for Virginia students affected by Massive Resistance following school desegregation and denied education as a result.

Ken Woodley, former editor of The Farmville Herald for 25 years and proponent of the scholarship program, said Marsh intervened and reasoned with the state during a time where the proposed scholarships were faltering.

“The next day he stood on the floor of the Senate and fought hard for it, and stood with us,” Woodley said.

Trending

Marsh, 84, said he remembers the one question that has ever stumped him. As a lawyer who has had decades of navigating legalities to bring justice for victims of racial discrimination, this was difficult to do.

In response to a question from an audience member, about what motivated him to pursue law, Marsh said that he had someone ask him a similar question he didn’t have an answer for — why he forewent the prospect of wealth and notoriety to help poor people.

“He stopped me,” Marsh said. “Because I don’t know why.”

Marsh said as a child, he walked 5 miles a day, every day, to receive an education in a one-room schoolhouse.

“I left home at 6 o’clock, got home at dark,” Marsh said.

He said having come from a background where he and others were affected by racial and educational inequality, his goal became helping others overcome similar obstacles.

Marsh said in response to a question from Museum Director Cameron Patterson about his collaboration with L. Francis Griffin, the Prince Edward County minister and civil rights advocate who he described as a “Renaissance man,” someone well read and invested in philosophy that shaped his work. Marsh said in the face of school closures by white supervisors, Griffin chose to fight back. Marsh recalls Griffin saying that if participants don’t “protect these children with everything you could, you’re less than a man.”