Meals tax on par with others

Published 11:27 am Thursday, November 17, 2016

Editor’s note: This story examines the history of the meals tax in Farmville and how it compares to surrounding areas in the state of Virginia.

Though Farmville’s meals tax exceeds those of surrounding communities, it is not unusual compared to towns of comparable size throughout the state.

Trending

According to town ordinance, the tax is levied on “all food, beverages or both, including alcoholic beverages purchased in or from a food establishment, whether prepared in such food establishment or not, and whether consumed on the premises or not, and without regard to the manner, time or place of service.”

Though many counties and towns in Virginia have tried and failed — or not tried at all — to invoke a meals tax, Farmville has had its tax in place since 1988, according to Town Manager Gerald Spates.

Farmville Treasurer Carol Anne Seal said towns and cities are able to approve the meals tax through a process with their councils. Seal said a public hearing must be held first and council votes on the levy.

Counties, on the other hand, are required to enact such taxes through a referendum on the ballot. In Buckingham, for instance, petitions signed by registered voters must be submitted to the clerk of the circuit court for a judge to approve or disprove for the ballot.

“The referendum would have to pass with enough votes on the referendum for the county to even consider the tax. ‘Enough votes’ is more ‘yes’ and than ‘no,’” Buckingham County Administrator Rebecca Carter said.

Trending

According to the Virginia code, following a successful referendum, the meals tax is brought before a board of supervisors. While “the tax shall be effective in an amount and on such terms as the governing body may, by ordinance, prescribe,” if the board or a petition set out specific uses for the tax, then the question on the ballot should have included that language.

Buckingham County has a storied history with meal tax attempts. Twice in recent years, county residents and supervisors have rallied to see a referendum pass in the county. Both efforts failed.

In 2012, the referendum gained enough petition signatures to be seen on the ballot, but was overwhelmingly rejected, with 68.63 percent of voters choosing “no.” In 2014, petitioners attempted, again, to get the referendum on the ballot, but couldn’t get enough petition signatures.

The 2014 petition would have had the meals tax used for “operational costs and capital improvements for education and public safety” and would have adopted an up to 4 percent tax on prepared foods and beverages.

Carter said she does not know if county supervisors or residents will approve a meals tax in the future.

Meanwhile, in Farmville, town council has continued to approve increases since it’s initial vote in July 1988 approving a 3 percent meals tax. In 1992, council members voted to increase the levy by one and a half percentage points to 4.5 percent. Then in 2003, two percentage points were added-making the tax 6.5 percent. In 2011, town council voted once again to increase the tax to where it stands now at 7 percent.

When purchases are made in Farmville on food, they pay not only this 7 percent charge, but also a 5.3 percent Virginia General Sales Tax, of which 4.3 percent goes to the state and 1 percent goes to the locality. This means Farmville-based food purchases can rack up a total tax of 12.3 percent.

Spates said the business get’s 3 percent of what it collects from the meals tax.

When looking to raise the tax in 2011, Assistant to the Town Manager and Clerk of Council Lisa Hricko said council looked to a number of localities in the state for guidance. They included the cities of Lynchburg, Danville, and Williamsburg; Orange County; and the towns of Ashland, Berryville, Big Stone Gap, Blackstone, Blacksburg, Bridgewater, Chase City, Dumfries, Lloyd, Haymarket, Kilmarnock, Fort Royal, Lawrenceville, Marion, Pulaski, South Boston and Rocky Mount.

Many of these localities have tax percentages comparable to or lower than Farmville’s.

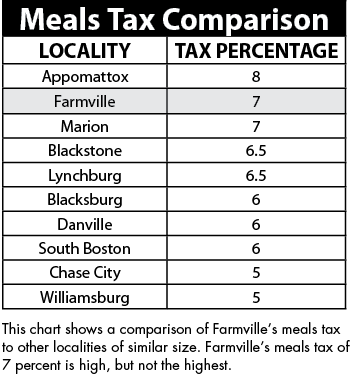

Chase City and the city of Williamsburg charge 5 percent for meals, while South Boston, Danville and Blacksburg charge 6 percent. In Blackstone and the city of Lynchburg, customers can expect a meals tax of 6.5 percent.

Marion has a 7 percent levy, along with Farmville. The nearby town of Appomattox charges 8 percent.

There are certain exceptions to Farmville’s tax. Food purchased through a vending machine does not apply, nor do meals served by churches for their members as part of their religions observances. Public or private elementary or secondary schools, colleges and universities may not charge this tax to their students or employees, nor may it be applied to food sold in “hospitals, medical clinics, convalescent homes, nursing homes, or other extended care facilities to patients or residents.”

Though there are different ways the taxes could be spent by localities, Farmville’s meal tax revenue is put directly into the general fund, Seal said.

The revenue collected from the meals tax has continued to increase in Farmville during recent years. The budget for fiscal year 2016-17 projects meals tax revenue income will be $2.498 million.

Seal said the difference between the projected income and what it actually ends up being is typically small.

The previous year’s taxation brought in a total of $2.402 million. In 2014-15, it brought in 2.342 million.

Seal and Hricko said they have heard no talk of the tax increasing any time soon.