In depth: Longwood University and football

Published 9:10 am Thursday, September 1, 2016

Editor’s Note: Longwood University supporters have wondered about the impact a football program might have on the university and community. Today, we look at the possible costs and how programs developed at other schools.

Longwood University has begun to assert itself as a competitive presence in the arena of NCAA Division I athletics, and some have wondered if the school may ever add a football program to its offerings.

As of right now, however, Longwood intercollegiate football is not in development.

“It’s genuinely not on the radar at all,” Longwood President W. Taylor Reveley IV said. “We’re working through a strategic plan that we came up with a couple years ago that didn’t contemplate something like football. (We) just finished up with the campus facilities master plan last fall with a lot of fanfare, which likewise, doesn’t contemplate football.”

Reveley, who played football at Princeton University, touched on a key difficulty involved in getting a program started.

“I love football, but it’s an expensive proposition,” he said. “The exact price point to get started at a (Football Championship Subdivision) level can vary a little bit, but it’s $20-$30 million pretty much no matter how you slice it or dice it, or at least that’s what, just in casual conversation, I’ve heard other universities put the figure at.”

Michelle Shular, Longwood’s senior associate athletics director for athletics administration, outlined some of the specific issues related to football Longwood would face.

“The obstacles to starting a program are initial start-up costs, lack of facilities for practice, competition and support services for the program, annual expenses to fund a Division I FCS football program and providing similar new participation opportunities for female student-athletes and the costs associated with adding those sports programs,” she said, alluding to the requirements brought about by Title IX with the last item listed.

Longwood does not currently have the money to overcome these obstacles, she said.

There would also need to be a plan in place to help sustain a football program each year.

“We estimate that the annual costs would be approximately $4 million, based on the annual budgets of football programs of our peer institutions at similar levels,” Shular said. “This does not include funds needed for a facility, which can vary greatly, but are in the multi-million dollar range.”

Scholarships are a key expense related to football programs. Some FCS programs do not offer scholarships, while those that do are allowed a maximum allotment of 63. Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) programs must have scholarships and are allowed to have 85.

Longwood Director of Athletics Troy Austin said he was unsure if Longwood would favor a program offering scholarships if it were pursuing football.

“A lot of schools started without scholarships because they look at it as a tuition exchange in that, if you have the startup money, you can probably get anywhere from 75 to 100 men who are paying their own way, mostly,” Austin said. “So, if you multiply that times $20,000 for in-state tuition, for them, that math is worth the $20 million it would cost to build the stadium and the probably $2 million in operating costs annually added, and probably another $1 million in staffing for the team.”

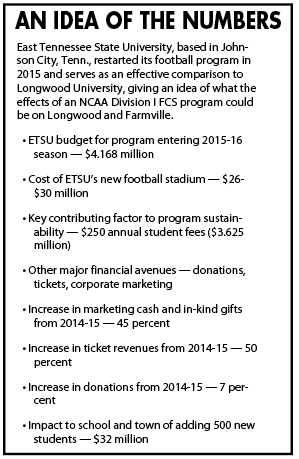

East Tennessee State University (ETSU), a public institution in Johnson City, Tenn., with between 14,000 and 15,000 students, re-started its football program in 2015 and serves as a comparison to give an idea of the possible impact of a Division I FCS program on Longwood and Farmville.

ETSU’s budget for its football program entering the 2015-16 season was $4.168 million.

Key to the sustainability of the program are individual student fees of $250 per year that contribute approximately $3.625 million annually.

“That was the real financial shot in the arm that was critically important to get football back at our institution. That’s obviously a quality base to get started with,” said ETSU Senior Associate Athletic Director/COO Scott Carter, adding gifts from donors, ticket sales and corporate marketing dollars are also important.

Gary Mabrey, president and CEO of the Johnson City Chamber of Commerce serving Johnson City and an ETSU alum, gave a snapshot of the projected annual financial impact the school’s new football program will have on the school and the town.

“The College of Business and Technology’s economic impact (study) said that adding 500 new students to our enrollment — football, band and associated students — would be a $32 million impact,” Mabrey said. “I think the city is going to benefit from a considerable amount of this $32 million.”

ETSU is building a football stadium Mabrey said will cost $26-$30 million.

“So, that’s a very direct expenditure that will be made in the Johnson City area that our businesses and others around will accrue,” Mabrey said.

ETSU’s 2015-16 fiscal year included a record-setting season in terms of corporate sponsorships, business partnerships and in-kind giving, with football as a key contributing factor.

The school accumulated $779,294 in marketing cash and $171,575 in in-kind gifts, totaling more than $950,000 — a 45 percent increase in revenue over the previous year and a more than 100-percent increase over the 2013-14 season.

ETSU set new all-time highs during the 2015-16 season for ticket sales, with its athletic events generating $821,448, a more than 50-percent increase from the 2014-15 season.

Also during the 2015-16 season, ETSU received the second-highest total of philanthropic gifts in school history with nearly $1.3 million.

“Longwood would likely experience increased revenues from various sources including ticket sales, merchandise, guarantees, concessions, parking and other areas,” Shular said, taking ETSU’s experience into consideration. “The Farmville community would most likely receive indirect benefits of these events in commercial enterprises such as hotels, restaurants, shopping, and from the increased game day traffic that would bring more people to the town.”

Longwood would need to find a place for a football stadium, and Ken Copeland, vice president for administration and finance at Longwood, addressed an obstacle on that front.

“There’s no place that we currently have our fingers in that would make sense for something of that magnitude,” he said, referring to a football stadium. “It would have to be someplace where there was traffic access and egress, and we just plain don’t have that any place that Longwood currently owns.”

While some see the issue of stadium placement as an obstacle, Austin disagrees.

“Longwood’s not landlocked,” he said, adding even landlocked schools are still able to find places to put a stadium; Georgetown University built one on top of a parking garage. “If they can figure out a way, we can figure out a way. I would say within the campus region — so if you look at where Lancer Park is, where Longwood Village is and where the main campus is — and you kind of setup that perimeter, there’s somewhere where you could find to put a football field.”

Part-time Buckingham County resident Ron Dowdy, who helped start the University of Central Florida (UCF) football program and was the lead donor for East Carolina’s football stadium, said adding football is a must for Longwood.

“Longwood is doing a great job with what it’s geared up to do,” he said. “But if you want to blossom it, you’ve got to have a football program.”

Dowdy downplayed the difference in market for UCF and Longwood.

“There is a market here for a football program,” he said. “Football programs, whether they’re a success or not, still bring in research dollars. … Nothing else will blossom this university except a football program.”

He acknowledged there is often local resistance.

“The local community is always the last one to jump on board,” he said, but added “it’s got to be done by the whole community.”

With the installation of a Division I football program, the potential marketing value for Longwood and Farmville would be significant if ETSU and Johnson City is any indication.

“A gross generality — but one that’s very real for Division I schools, is when your school — your logo or whatever is shown on national TV, there’s a marketing value to that,” Mabrey said.

Shular said a thorough feasibility study would provide the most accurate estimate to the potential revenues and marketing value of a football program for Longwood and the community.

Farmville Mayor David Whitus echoed this perspective. While he declined to give an estimate for the town’s potential revenue, he indicated the impact, based on the experience of other communities, is typically positive. He encouraged a unique approach that could ultimately lay the groundwork for Longwood football.

“I would like to see more community spirit for at least existing Longwood teams, and then maybe in generations to come, there might be a possibility of seeing that football team,” Whitus said.