‘The Vagabond’ comes home, book reveals mystery of Stanley Park

Published 5:36 am Thursday, March 31, 2016

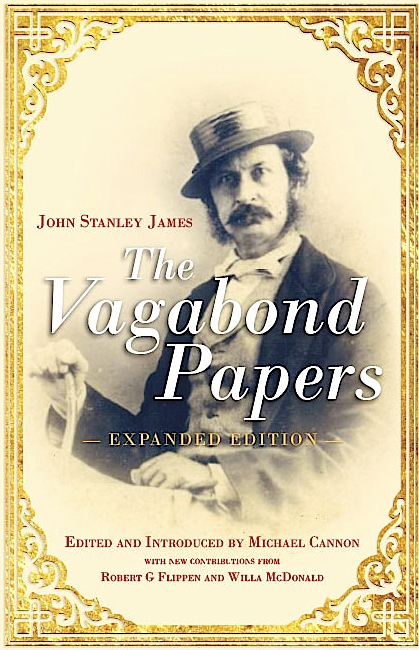

- Bob Flippen detailed John Stanley James’ time in Farmville in “The Vagabond Papers.” James, who changed his name to Julian Thomas after moving to Australia, was named to the Melbourne Media Hall of Fame in 2012.

Longwood University students housed in Lancer Park, formerly Stanley Park, live in the shadow of a Victorian mansion that once sat atop the bluff overlooking the Appomattox River. John Stanley James, a mysterious Englishman who came to Farmville in 1875 and left just as mysteriously six months later, built it. Little was known about James or his mansion until Bob Flippen brought the facts to light in “The Vagabond Papers.”

Flippen followed “The Vagabond” as James was later called, to Australia where he became a famous journalist and was ultimately named to the Melbourne Media Hall of Fame.

Trending

“This has been a lifelong research project,” Flippen said. “It started back when I was in college at George Washington University. I’d come home on break and ramble along the banks of the Appomattox River — and there was this house.”

Bob Flippen discovered the Victorian mansion on the hill overlooking Farmville as a college student “rambling along the banks of the Appomattox.”

“The Vagabond Papers” continue the narrative: “Emerging from a shadowy canopy of forest growth through a forgotten section of Farmville, there suddenly appeared a pasture, and crowning a tall hillside, the ghostly image of the Stanley Park mansion . . . then and there I vowed to unravel the mystery of the deserted mansion.”

Flippen, an education specialist for High Bridge Trail State Park, continues to research Farmville history as well as write and sell books.”

“The house was still there but unoccupied,” Flippen said of his early interest in the mansion. “I knew the owners and was able to walk inside the house with its well-preserved plaster walls and climb the stairs to the fourth floor. There the panoramic view of the countryside gave me a new perspective of the area’s geography. It was the perfect refuge for a young romantic who then vowed to unravel the mystery of the mansion.”

Flippen began his research with The Farmville Mercury, precursor to The Farmville Herald, on microfilm at the Longwood University Library.

Bob Flippen marks the spot where John Stanley James built his mansion in 1875. Stanley Park, as it was once called, is now home to Longwood University students living in Lancer Park housing.

Trending

On Aug. 19, 1875, The Mercury reported: “Mansion completed in ten weeks — As an instance of the enterprise and go-a-headishiness of our town, we refer to the fact that the elegant mansion of Dr. Stanley James in Stanley Park has been put up and ready for occupancy inside of ten weeks.”

Flippen’s book describes the mansion: “The house included a number of unique architectural features, most visible was the tower occupying the third and fourth floors. The first floor featured six rooms with two large bay windows and hidden sliding pocket doors enabling two rooms to become one great room perfect for dining or entertaining. A narrow servants staircase wound from the first to second floor, which included three large bedrooms.”

“What fascinated me was the Englishmen who came here after the war,” Flippen said. “John Stanley James was one of them.”

James came to Farmville in early March of 1875 accompanied by Gen. James R. Slayton, editor of a New York paper, who had been invited to visit Farmville by Mercury editor Joseph Andrew Horner St. Andrew.

“I think it was an economic thing to recruit English colonists to this area,” Flippen said.

James was welcomed to Farmville by members of the Farmville British Association. In short order, James was named to the bank board, acquired a wife and built his mansion overlooking Farmville. By September James was advertising for Stanley Park Academy for “a select number of boys under 16 years of age,” naming himself principal.

James was putting down roots in Farmville, or so it seemed.

Flippen couldn’t help but wonder — what prompted James to leave town with so many things going for him.

“I was determined to figure this thing out,” he said.

Flippen turned to the Internet, and what he discovered was intriguing.

“James went to Australia and changed his name to Julian Thomas,” he said. “ I found a list of his publications and started buying them.”

“James became very famous as a writer and journalist,” Flippen said. “He was a pioneer in immersion journalism and wrote about topics taboo in the Victorian era, like the treatment of prisoners.”

To write about prisons, Thomas took a job at the prison — “immersion journalism.”

As to James’ sudden departure from Farmville, Flippen’s research offered well-founded clues.

“As a banker James was a miserable failure,” Flippen said. “When his friends wanted a discount on their bills, he co-signed the notes.”

The money lost when friends failed to pay did not come out of James’ pocket.

“He married a rich widow, Carolyn Lewis,” Flippen said. “James was impecunious. When he built his house, it was with her money.”

In the courthouse Flippen found confirmation of “irreconcilable differences” resulting from James’ generous disbursement of his wife’s funds.

“James basically gave his wife the house, land, furniture and content and relinquished her from ‘any further debts,’” Flippen said.

The final leg supporting James’ brief stand in Farmville collapsed after the editor of the Farmville Mercury engaged him in a letter-writing controversy.

“James constantly advised others to become American citizens,” Flippen said. “Some were agreeable, but others seemed content to be British subjects.”

The Mercury editor was one of the latter.

“When James wrote his last letter to the editor and dropped it in the mail, he was already packed and gone,” Flippen said.

Flippen speculates that James’ wife returned to Richmond. The mansion changed hands over the years and finally was sold and dismantled.

Flippen’s research on James was recently recognized in Australia; he has been invited to speak there in the fall.

“I’ve written this to satisfy the curiosity of the Australians and introduce James to the American public,” he said.

John Stanley James no doubt would be pleased. While the pioneer of immersion journalism is gone, his legacy lingers, forever immersed in Longwood’s community of learning — once known as Stanley Park.

‘The Vagabond Papers’ ($25) is available from Bob Flippen; call (434) 392-8300 or email svhp@kinex.net.