A Thanksgiving menu — 3,000 years ago

Published 2:28 pm Thursday, November 19, 2015

- Who’s coming to Thanksgiving dinner? Dr. Jordan has the answer — and the menu may surprise you.

The Thanksgiving holiday we will celebrate in Farmville next week did not exist until the year 1621 when Pilgrims in a little village called Plymouth, Mass., had an excellent harvest and decided to hold a “harvest festival.” Thus was born our modern tradition of celebrating the bounty of nature and our lives on the fourth Thursday of each November.

Long before 1621, the first Americans, the Indians of Virginia, had similar festivals for the same purposes. The “Green Corn Ceremony” was celebrated each year when the corn crop was harvested. What would have been “on the menu” of native Indians of the Farmville area in the autumn each year?

Thanks to archaeological excavation at four sites near Farmville — Anna’s Ridge on the Willis River, the Smith-Taylor Mound on the Appomattox River and the Willis Mountain Cave and Morris Field sites in Buckingham County, we can attempt an answer.

Trending

Let’s see what’s to eat 3,000 years ago!

We might start our meal with an appetizer of berries — and what a choice we would have: raspberries, blackberries, blueberries, gooseberries and serviceberries. Some nuts (chestnuts, walnuts and chinquapins) might follow along with seeds — Indians had domesticated the sunflower to harvest their nutritious seeds. When the sunflower seeds ran out, there were all those pumpkin and squash seeds. To add a bit of sweetness, Native Americans manufactured sugar and syrup from the sap of maple trees and sweet tea from the sassafras plant.

Our main dish very likely would consist of corn in some fashion — early European colonists recorded 42 different corn-based recipes used by Indians.

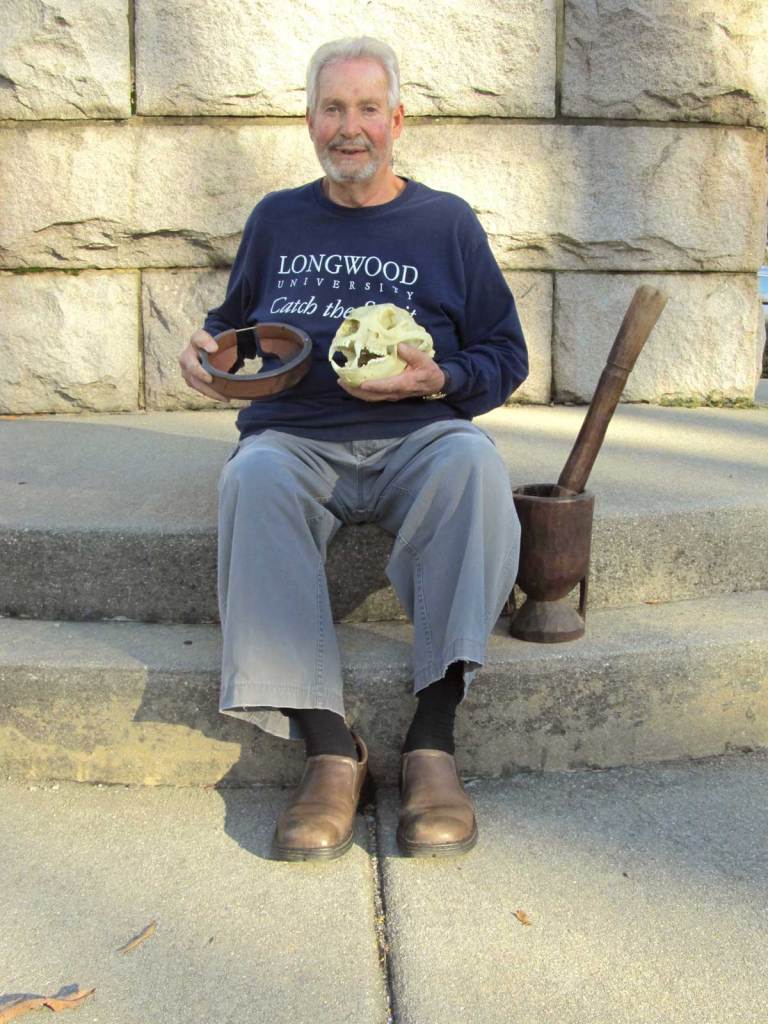

Cornbread was made by cracking the kernels in a wooden mortar and sifting it into a fine meal through a basket. The flavor of the bread was varied by adding mashed pumpkin pulp or jack-in-the-pulpit, seeds, nuts or berries.

The meat side of the main dish might be venison, turkey or squirrel, but the most highly prized by the Indians was black bear meat with its thick juicy layers of fat. It was cooked in earthen pots and the oil was extracted and used as a condiment, a cooking oil and even as a cosmetic and ointment. All meat and fish were thoroughly cooked; Indians never ate it raw. So surely we would enjoy a soup or stew made of raccoon or opossum, rabbit, turtle or fish.

The Indians of 3,000 years ago knew a lot about processing, cooking and preserving food — maybe even more than we do today since they did not have refrigerators, microwaves or the frozen food aisle at Food Lion!

Trending

Drying or smoking preserved the food for later use. Certain foods had to be carefully processed or they would be dangerous to eat. Acorns, for example, had the poisonous tannic acid leached out of them by soaking in baskets in a stream before they were pounded with a pestle in a mortar to make flour for bread. Persimmons (think Persimmon Tree Road in Farmville) were gathered before animals ate them in the late summer — they were carefully stored until the winter frosts changed their astringent bite to a delicious date-like flavor. Anyone who has tried to eat an under-ripe persimmon will remember it as an unforgettable experience.

Foods could also be preserved by salting. Indians collected salt from soil at salt “licks” or mineral springs (like Farmville’s Lithia Springs) and added ashes from burning hickory wood, bones, shells, horns or antlers to give their dish savor.

When you travel about Southside over Thanksgiving weekend, look about you. Whenever you see a corn maze, a pumpkin jack-o-lantern, a shock of “Indian corn” or sit down to enjoy cornbread and cranberries or the latest new taste flavoring almost every item in the kitchen, pumpkin spice, (my own daughters love it!) you know who to thank — our Virginia ancestors, the Indians.

You are living a part of the lives of these Indians when you read or hear the following Indian words: pecan, persimmon, cornpone, squash, chinquapin, hominy, hickory, chipmunk, opossum, raccoon and succotash.

Enjoy your Thanksgiving — and thank the Indians also!

DR. JIM JORDAN is professor of anthropology at Longwood University. His email address is jordanjw@longwood.edu.