Service through the letter of the law

Published 10:10 am Thursday, September 3, 2015

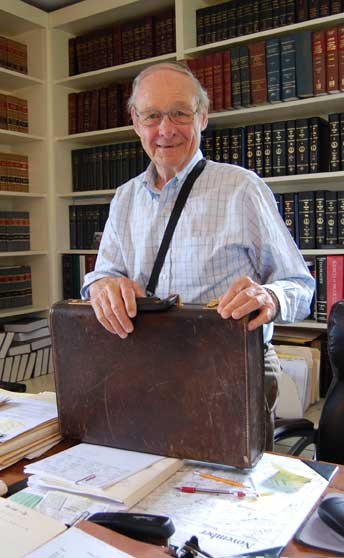

- James Pendleton “Penny” Baber, who has deep roots in Cumberland County through his family and public service, stands with his briefcase in his law office.

A musty smell of old papers and numerous bound volumes of Virginia criminal and civil codebooks enclose an old wooden desk that he handmade out of materials from numerous homes across Cumberland County.

The atmosphere of his law office, trimmed with photos of his family and fox hunting days, includes stacks of files and court paperwork that he’s been handling since his days as a young man.

As he slowly makes his way from the circuit court clerk’s office, located about 100 yards in front of his office, he greets his assistant, smiles and hands her a copy of a property deed he just finished recording.

It was a short stroll down a familiar path that 78-year-old James Pendleton “Penny” Baber has made thousands of times in his over 50 years as a practicing attorney in Cumberland.

The bespectacled grey-haired lawyer, who served for years as the Cumberland commonwealth’s attorney, has handled heaps upon heaps of civil and criminal cases over his days in practicing law.

Baber’s office — the former farmhouse of Thornton and Fannie Foster — sits in the middle of the county right beside the courthouse, a familiar place to the Cumberland native.

Baber, who was born in his grandmother’s house in Columbia, has deep roots in the county. In 1915, his grandfather moved from Albemarle to the county that Baber would later serve through public office. After graduating with 18 others in his class in 1954 from Cumberland High School, Baber attended the present-day University of Richmond.

There, he studied English and graduated in 1958. “It was easy,” he laughed, explaining why he chose to be an English major.

Perched in his office chair behind his wooden desk, he recalled that before entering law school at the University of Virginia, he met his late wife, Carolyn Stonnell, who encouraged him to get his law degree.

The initial push to be a lawyer, said Baber, came from his old friend Richmond College buddy Johnny Rennolds. It was their idea to join the Navy, then attend law school together.

While Rennolds was able to join the Navy, Baber was rejected due to his hearing. “And I never got drafted, so I had to go to law school,” said Baber, smiling, adding that he paid $275 per semester while studying.

While attending UVA, Baber passed the state bar exam during his second year in school, and, shortly thereafter in 1961, he came back to Cumberland, starting his own law office.

“I didn’t [even] have a secretary,” said the devout Episcopalian. “I just hung up a shingle and rented some space over in that little building over there,” he said, pointing his finger towards U.S. Route 60. “I rented it from the county, actually,” he said. Two years down the road, Baber sought to be the next commonwealth’s attorney for Cumberland.

And five votes would keep him from fulfilling his ambition. In 1963, incumbent William C. Carter would defeat the young Baber.

He was beaten, but not discouraged.

“It wasn’t a terribly big deal. An election is more of an ego trip than anything else,” he said. “That many people didn’t know me, I guess,” he said.

It only took four more years for people to get to know Baber; in 1967 he ran again and defeated Carter.

Baber would be re-elected through every election cycle until 1983.

As commonwealth’s attorney, Baber began his political career making $300 a month. The office was part-time then, which allowed him to maintain his private law practice.

“I don’t know,” he responded when asked why he ran in the 1960’s. “It was just something to do, you know. It’s a sort of practice builder.”

He said he really didn’t enjoy prosecuting people. “That’s not fun,” he said.

While he was prosecuting, he said he figured that people came to him for advice and guidance. “Most people that talk to a lawyer have got a problem, you know?”

Baber said he found it unpleasant dealing with other people’s problems. “The rewards … are doing simple things that make the business go along smoothly.”

Another thing that he didn’t like was being in the courtroom. “When you get to the courtroom, you’ve already lost. I mean, it’s because you couldn’t work [it out].” He said working out issues out of court was the nature of the system.

“Once you get over it, it’s alright,” he said handling complicated cases. “I am personally averse to controversy. I simply don’t like it. I’m uncomfortable with controversy,” he said.

The attorney, who still practices and defends people across the area and in Cumberland, says he’s never had a strong passion for any one thing in life.

“[D]eveloping a sense of optimism,” he responded when asked what brought him satisfaction in life. “And, it’s a good thing to be a human being. And … if that’s all you can be then that’s good.”

“I don’t know why we are so concerned about what’s going to happen when we die,” Baber added. “We’re obviously not going to be aware of it anyway,” he laughed.

Baber said he hopes that some people will have a recollection of him as time moves on. “I obviously haven’t done as much as I could’ve done. I feel I made a good faith effort. …”

His satisfaction also lies in developing a sense of acceptance “of the value of what we are.”