A Boy's Life Took Off Behind Horse And Plow

Published 2:33 pm Thursday, January 17, 2013

FARMVILLE – Larry O. Spencer wasn't a general as he walked toward the plow on his grandfather's farm in Red House nearly half a century ago.

There weren't four stars and salutes from everyone he encountered.

Just a horse and a plow that had been harnessed to his grandfather all morning.

A hot summer morning, and his grandfather was taking a quick break in the cool of the surrounding woods.

A boy, a horse and plow.

A boy who, living amid the pavement of the nation's capital, knew nothing about horses and not a thing about plowing.

But he wanted to help his grandfather, taking a step, then another, toward the plow and the horse.

Destiny was waiting for its furrow in the young boy's life and a harvest far distant over the tree-scaped horizon.

The man who would become a general spent every summer of his boyhood in Red House, driven from his Washington, D.C. home by his father, the late Alfonzo Spencer, a native of Red House, and an Army veteran. The Charlotte County summers were filled with classic boyhood fun-after work in the family tobacco field-fishing and playing with his cousin Bernard.

But this particular summer so many years ago was different. Bernard was visiting other relatives in Philadelphia so young Spencer and his grandfather, P. A., were that summer's dynamic duo.

Except the man now in line to advise the President of the United States, the Secretary of Defense, and the National Security Council was a rather introverted youngster, content to sit and listen to what the world had to say and look at what it had to show him.

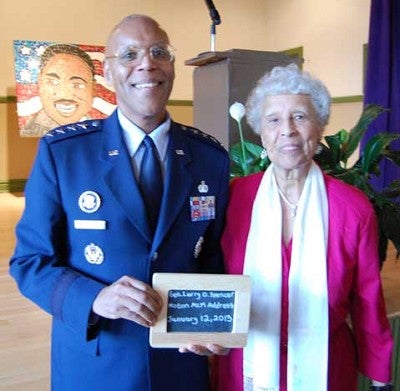

“It was a little bit awkward for me,” General Spencer told a filled auditorium at the Moton School Civil Rights Learning Center (Moton Museum) during his keynote speech for the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. commemoration, “because it was always me and Bernard and now it was me and P. A.”

Nobody knew that the young boy would be appointed by the President of the United States as the second-ranking officer in the U.S. Air Force in 2012.

That summer in the early days of the 1960s provided a turning point in the youngster's life, however, and one that still brings a tear to his eyes and a catch in his voice as he tells the story of the plow, the horse, and P. A.

Without Bernard, the young Spencer was able to see his grandfather “in a different light than I had seen him before. He was a deacon at church and he went all over to church services and he dragged me with him and when we were in the car or truck-for the most part I was introverted, not a big talker-I would just sit there and not say a whole lot and he started talking to me and he started asking me questions and he would say 'What do you think about that? or 'What is that over there?' or 'How does this work?'”

When he wasn't riding with his grandfather from church to church, the youngster was tagging along to watch him do the farming.

“I would get up every morning…and sit on the back of that tractor.”

Until the day of the plow.

“I don't know a lot about a lot of things, and I certainly don't know anything about plowing. I didn't then and I don't now,” he said with a smile.

But he does know something more important. He knows something critically important and he knows it very well.

“One day we were out in one of the fields some distance from the house. Just he and I. And he was plowing rows. And I'm sitting there watching him. At one point he had plowed about half the field and he stopped and…I assume he went to the bathroom. Went off in the woods. And so I'm thinking, 'Okay, we've got this different relationship here and I want to impress him. And how hard could it be to get behind a horse and plow a row?'”

Life often teaches that if you ask and then answer your own question, without waiting for wiser counsel, you may get a surprise, and one that can sometimes change your life.

“So, when he disappeared into the woods, I strapped on this plow and I started plowing this row,” General Spencer said, standing on the stage where Barbara Johns led the historic strike at R. R. Moton High School, with his mother, Prince Edward County native, Selma Gaines Spencer, among those students who took a stand that planted the seeds of a new day in America.

As the horse began to pull the plow and the young boy strapped to the plow, two points occurred to the man who would grow up to become Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force. “Number one-I knew how to make the horse start but I didn't know how to make the horse stop. So I knew how to make the horse go forward but I hadn't thought about how I was going to stop it and turn around.

“I also didn't understand there's a trick to maneuvering a plow straight. I didn't understand that, either. So I got the horse to move forward and I'm going behind the horse and this plow,” he said.

“And I'm cutting straight across the row (P. A.) just plowed. I had no idea how I was going to stop the horse, and I was really scared. For a lot of reasons,” the general said. “One reason is I was afraid I had ruined all his work. And, two, we were off in the woods-there's a lot of switches out there.”

General Spencer can smile now, the audience cheerfully laughing with him.

But there were no smiles on the young Spencer's face that day so long ago, nor any laughter in his heart at that moment.

“As I was getting to the end of where P. A. had plowed, the horse just did not stop, and I am convinced that had I not stopped that horse I'd still be behind that horse, plowing across country by now,” said the man who flies across country instead.

Then his grandfather came out of the woods.

“And he yelled my name and I turned around, but the horse kept going, so I was starting to stumble so I said 'whoa', you know, just to myself,” he said, the smile on his face lighting up the room and the audience totally in tune with the story and the storyteller. “And the horse stopped. So I got that part figured out.”

An accidental 'Whoa' not even meant for the horse stopped the plow from cutting across any more of his grandfather's rows.

But the woods were still full of switches.

“The next thought I had was my P. A. was on his way walking toward me and this is not going to go well,” General Spencer said, his mother seated on the front row, along with several rows of relatives.

Switches.

The woods were full of them.

And he had just plowed across a morning's worth of rows dug into the earth by his grandfather.

Hard work.

Under a hot sun.

But a sun full of illumination, not simply heat alone.

“He came up to me,” the general said, “and I think he really appreciated the fact that I would take the initiative to try to do this on my own. And so I wasn't sure what to expect.”

His grandfather knew exactly what to do.

Knew precisely what words to speak.

Words that would plow a deep row in the young boy's life.

Words that would sow good seed.

Words that would bring a lifetime of harvest as the young boy grew into manhood and recalled the days on his grandfather's farm and that day in particular.

A four-star general might have been planted that morning.

“I will never forget what he said. He said, 'It's okay to try, and fail. It's not okay not to try,'” General Spencer said of the words that lifted him, erasing all fear and thought of switches, a philosophy of life bequeathed at that moment through a grandfather's encouraging love. “And I will remember that the rest of my life.”

The general raised his eyes, looking out at all the faces at Moton, then glanced again at the room in the former school where the civil rights movement began. What happened in that space, and beyond, on April 23, 1951 “is something we can all be proud of because it changed history, it changed the way this country was going, it woke this country up,” he said. “It led to desegregating our schools, and so we should all be proud of that, not just the folks that were a part of that, but all of us should be proud of that.”

Telling his audience that it is “an honor and a privilege to serve” his nation, the four-star general who is plowing far more than a field with his career said, “I look forward to going forth from here even more inspired than I did when I came here, to try to take those opportunities that happened here to make a difference.”

Then the 58-year old general, feeling life's plow firmly in his hands, planted seeds of his own.

“Everyone in this room has that capacity to make a difference as we go forward. It's okay to try, and fail,” he said, his voice thick with emotion, recalling a horse and a plow in Red House, and a grandfather's guiding love. “It's not okay not to try.”